Spinning-Weaving Exhibit

Spinning Wheels, Niddy Noddies, Yarn Winders, Scutching Boards, Hatchels, Carders, Weasels, Flax Breakers and Floor Looms!

Over the past two hundred years, the art of spinning natural materials into thread and weaving thread into textiles and clothing has changed with the Industrial Revolution and yet... it has stayed the same.

We can now purchase our clothing from factories all over the globe. These factories are filled with machines and devices that cleverly prepare fibers for mechanical processing. Hardly a human hand may touch your garments in their making. But here, we will examine the process of making textiles by hand, sharing the tools saved by those who loved their craft.

People still lovingly raise lambs, shear sheep, spin wool and weave on old fashioned looms. The Potsdam Museum is fortunate to have a collection of such tools. Marion Channing states in her "Magic of Spinning" book that in 1800 there were approximately three and a half million spinning wheels in the United States alone! Not so many survived as they were large and cumbersome.

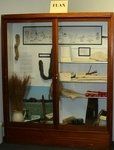

On display were an assortment of spinning wheels for making wool and flax wheels for making linen. Also used in the process of flax preparation were flax breakers, large primitive wooden tools used to smash the dense woody flax stalks. Many of the tools in the museum collection were used locally and lovingly preserved.

The exhibition opened May 22nd (2011) through the summer and fall. We invited students from the middle schools to view the exhibit and try their hand at spinning with a drop spindle and weaving on the small floor looms used for classroom teaching. Programs and demonstrations will be posted.

From Seed to Fabric

Creating linen from the flax plant

Why didn't the colonists simply purchase fabric from their mother country? English goods were considered to be superior to those of North America and the colonists were content for a time to buy product from Britain. However, the British, in an effort to prevent the colonists from manufacturing their own goods put high tariffs on looms and spinning wheels and passed acts forbidding the export and sale of American made textiles. The colonists, being a very independent people, began growing flax and making their own fabric to reduce their dependency on British imports.

On display were an assortment of spinning wheels for making wool and flax wheels for making linen. Also used in the process of flax preparation were flax breakers, large primitive wooden tools used to smash the dense woody flax stalks. Many of the tools in the museum collection were used locally and lovingly preserved.

The exhibition opened May 22nd (2011) through the summer and fall. We invited students from the middle schools to view the exhibit and try their hand at spinning with a drop spindle and weaving on the small floor looms used for classroom teaching. Programs and demonstrations will be posted.

The seeds of the flax plant were sown early in the spring and close together to prevent the weeds from developing and to also allow the plants to support each other as they grew taller. The flax plant could grow to be four feet tall and was ready to harvest when the lower leaves died and fell to the ground, about three months. The plant was then pulled from the ground, the dirt tapped from its roots and bundles formed and stacked together into a "stook" or "shock" which looked like a tepee in shape, and left to dry.

After the plant was dry, the seedpods were removed from the plant by pulling it through a rippling comb. Some of the seeds were saved to plant the following year. The excess seeds were crushed for their oil (linseed oil) which might be used for making paints, printers ink, medicines, burned to light lamps, or used in cooking.

The flax straw was then "retted", which meant it was either left out in the fields to be moistened by the dew, or placed in ponds, streams or even tubs of water so the connective gums would break down. The flax left in the fields took up to six weeks to break down and would be silver colored, while that retted in a pond, stream or tub only took about a week and would be a golden color.

The flax was dried again, then put through a flax brake, smashing the flax and breaking the woody stalks. The flax was then swung over a scutching board and beaten and scraped with a scutching knife, removing the remaining stalk pieces. Now it was time to separate the fibers by drawing the flax through a series of hatchels (also known as hackles or hetchels). The hatchels ranged from coarse, to medium, to fine, the coarse having heavy teeth widely spaced, the fine having fine teeth close together and the medium in between. As the flax was drawn through the progressively smaller teeth, the flax fiber became finer. The long, fine fibers were spun into a strong thread called linen. Linen could be woven into a long lasting fabric that could be used to make clothing, sheets and other products. Constant use would make the fabric softer. Linen could also be woven with wool to make "linsey-woolsey" fabric used in clothing.

Each year sheep are shorn. The wool fiber ranges in length from two to twelve inches depending on the breed of sheep. The shorn fleece is skirted to remove the leg and belly wool, as well as any dirty wool. The fleece could then be washed carefully in hot soapy water and dried, or it could be carded and spun without washing it first. This technique is called "spinning in the grease". Sheep have oil in their skin that lubricates the fiber and keeps their skin dry when it rains. Lanolin, used in hand lotion, is found in sheep's wool.

Before spinning the wool into thread it needs to be cleaned of dirt and vegetable matter (like hay and straw). The fibers also need to be straightened to produce suitable yarn. One way to accomplish both cleaning and straightening the wool fibers is by carding. This was a job done by colonial children between the ages of three and four years old.

Carding: The wool is placed in small handfuls on the wire teeth of the cards, then one card is pulled across the other, brushing the wool free of dirt and tangles. The wool is then removed form the cards and rolled into a rolag.